One of the trickiest things in life, is staying awake.

I mean this literally – who, once they’ve reached the appropriate coffee-drinking age, isn’t in some way addicted to caffeine? Doesn’t wake, dough-eyed and creaky, unable to face the day without that sweet hit of stimulant? (Lots of people, I’m sure, but not too many that I know).

And I also – being the somewhat earnest, frowny creature that I’ve been at least since primary school, if the photo record is to be believed – mean it figuratively.

Life has so many bits to it. Family, house, car, insurance, superannuation. Job security. Marriage. (Or lack thereof.) Children. (Likewise.) Friends. Exercise. Elections. Natural disasters. Christmas.

And then, of course, there’s death.

It’s a lot to hold in the balance.

I was a rather single-minded, if generally under-occupied, teenager. Didn’t do hobbies; wasn’t one for socialising; would seek to fix just about any mood with sugar (forget exercise). But I did love school. Not the social stuff – that sucked. But the classroom, the assignments, that pop of a moment when things fell into place – it was great. I liked how structured everything was. I enjoyed school report time. Lots of other things were falling apart, but at school I approached my life with a clear sense of what I wanted; I felt as if I were truly awake.

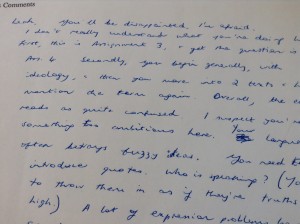

I was, of course, a fool. As one of my university lecturers would later write on a particularly rushed, ill-thought out essay: You’ll be disappointed, I’m afraid. I don’t really understand what you’re doing here … Your language often betrays fuzzy ideas … and you clearly don’t quite understand terms like ‘ideology’, ‘langue’, and others.

It turns out that you can’t just string together a few vaguely clever-sounding sentences, and call it an essay. Any more than you can string together a few wildly unrealistic plans, and call it a life.

One actually, unfortunately, has to work at things.

At some point I must have noticed that Hazel Rowley, who wrote those words on my junky essay, had written a book. There was a promotional poster in her office. I’d never heard of Christina Stead, and didn’t know that the biography Hazel had written of her was internationally acclaimed. I enjoyed Hazel’s tutorials, though – the way she’d stride energetically around the room, apparently unaware that such enthusiasm was rather, well, embarrassing – and I took every opportunity to stop by her office, discussing essay topics, getting help, negotiating extensions.

When Hazel told me she was leaving Australia – she seemed surprised to have been offered a sizeable advance to write another biography – I was focused, pretty much, on myself. My helper was going away – to write a biography of some guy named Richard Wright, apparently. I didn’t really care what for. What I knew was that since the disappointing essay, Hazel had helped me write better ones – and had written some nice things on them, too. She might be able to help me get to where I ultimately, secretly, wanted to be – to a life as a Proper Writer.

Eventually, I got around to reading Hazel’s books. They were incredible. Her language was sharp, her research exhaustive. She was smart. Really, really smart.

Hazel died in 2011. She was 59. That day I sat at work – thinking about my children’s schedules, the dinner to be made, the to-do list on the post-it note next to the computer – wondering how to feel about this event. The obituaries talked, of course, about her remarkable contribution to literature. About how she made her mark in Paris, New York. Her uncompromising standards. Her insight.

What I felt, was sad. And disappointed – that she hadn’t been able to go on working, and writing. And that somehow, in spite of the nice things she’d written on my essays, I’d stopped.

It took me a while to realise that I had things arse-about. The relationship I had with Hazel was enormously important to me. She encouraged me, and she gave me a window on another kind of life. But although I took the time to tell her how much I enjoyed her books, and ask her for the occasional academic reference, I don’t think I ever thanked her for teaching me. For sharing with me the pleasure of the act of writing, of thinking, of making sense.

Next to that, my achievements (or lack thereof) are little more than a list.

A friend of mine recently put it like this: With six billion people in the world the odds are pretty stacked against any of us, or anyone we know, being truly outstanding. Happy? Now that is an option. So is fulfilled. And creative. And, occasionally, in a funk. Of course this friend is already outstanding – the point is that the proof, to mangle a cooking metaphor, is in the doing.

In other words, getting on with the big stuff – looking after ourselves and our families, reading, scribbling, staying awake – is what there is. We are what we do. The rest is window dressing.